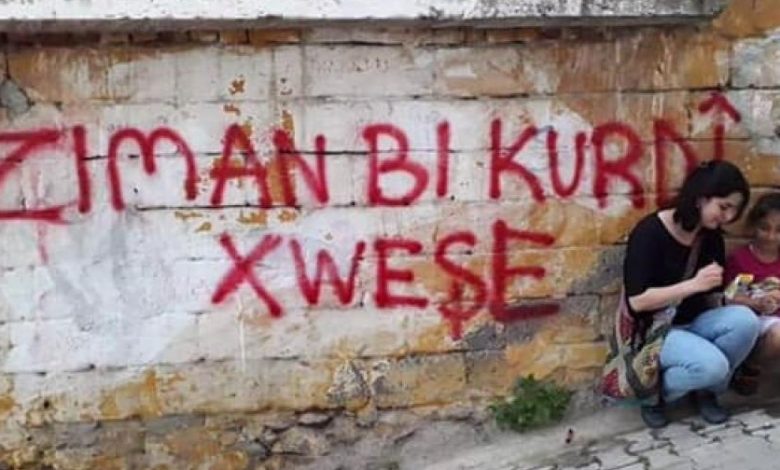

Kurds push for Kurdish courses on the language learning app Duolingo.

The best option for Turkey’s Kurds, a population of between 15 and 20 million, to learn Kurdish is private language courses.

Concerned that an increasing number of Kurds in Turkey cannot speak their native language or have difficulties with their reading and writing, nine members of the sizeable Kurdish community on Twitter came together to take matters into their own hands, and to push for a Kurdish course on the language learning app Duolingo.

“We believe that language is important in every aspect of our lives, because it allows people to communicate in a manner that enables the sharing of common ideas,” volunteers Servan Amed and Îsheq Hemrînî, who also run the initiative’s twitter account, told Ahval. “Kurds, the largest minority in Turkey, cannot receive education in their own language.”

Schools in Turkey must provide education in the country’s official language, Turkish, with an exception made for minorities recognised in the Treaty of Lausanne, which fixed most of the borders of modern Turkey and guaranteed the rights of religious minorities in Turkey and Greece, but failed to mention Kurds.

The best option for Turkey’s Kurds, a population of between 15 and 20 million, to learn Kurdish is private language courses.

To learn Kurmanji, one of the four main dialects of Kurdish, spoken in Turkey, Syria, and parts of Iraq, Turkish citizens can take courses offered in some universities and NGOs, made possible after amendments to laws restricting the use of Kurdish in 2003.

The Kurdish Institute of Istanbul, founded in 1992, launched the first language courses in 2004. Thousands have taken their courses since then, some learning the language well enough to teach, former president of the institute Şefik Beyaz told Ahval.

The Duolingo Kurdî team thinks the app might provide a low-effort alternative to the existing courses. “Education in the native language is the only way to stop (a decline in language proficiency) 100 percent,” they said, “but everyone with an internet connection has access to Duolingo.”

However, there was a time in Turkish history when merely stating these opinions could get them into trouble.

“Assimilation policies legitimised through laws put pressure on Kurds from 1925 onwards,” Beyaz said, and Kurdish speakers faced fines and persecution.

From the 1950s, the pressure on Kurdish speakers was partly relieved, but returned with a vengeance after the 1980 coup and resultant military rule. The language, and even the use of Kurdish names, was banned once more.

“Until the 1990s, it was a problem to speak of Kurdish language education, let alone education in the mother tongue/Kurdish,” Beyaz said. The official ban on Kurdish was lifted in 1991, although the spirit of the law lingered.

In 2009, during the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) first decade in power, Turkey’s state broadcaster TRT opened a Kurdish language channel. In 2011, Kurdish language and literature departments were established in three universities.

Many in Kurdish society have joined the demand for education in Kurdish since then. “A significant portion of Turkish society viewed this demand favourably as well, but no laws were passed to allow education in the mother tongue,” said Beyaz. Practical efforts for Kurdish language education took precedence, while demand for integration of Kurdish in public life continued in the background.

The first post on Duolingo Kurdî’s forum thread was made in 2015, the same year that a peace process between Turkey and the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which many hoped would bring an end to four decades of bloody conflict, collapsed.

Although the Duolingo team told Ahval they had not faced much antagonism, “apart from a few troll accounts,” – which is common with any content related to Turkey and Kurds – they have also not been able to attract any major response, negative or positive.

The team has some 20 volunteers, including linguists and translators on top of bilingual people, which they say appears to satisfy Duolingo’s criteria, as there are “courses in different phases of preparation,” they have found, including Yucatec for Spanish speakers, Esperanto for French speakers, and English for Hebrew speakers, which have three, seven and zero current contributors respectively.

“We will continue our campaign (for a Duolingo course) until we succeed,” the team said – a sentiment echoed by many people invested in the preservation of Kurdish culture and language.

Pro-Kurdish candidates won 64 mayoral seats in five provinces in 2004 and, taking advantage of the recent easing in restrictions against Kurdish, they kickstarted official efforts to provide bilingual services for the first time. Continuing with 102 municipalities won in 2014, intensified efforts “fortified their legitimacy,” Beyaz said, “while achieving competency and expertise.”

However, between 2015 and 2019, 95 of these mayors were dismissed and replaced with government appointees. “The first thing they did was to end activities related to Kurdish,” Beyaz said.

Another 40 out of the 65 mayors elected in 2019 faced the same fate, along with the institutions they built in their respective municipalities. “Their activities were also sabotaged,” lamented Beyaz. Bilingual day care centres, women’s shelters, and theatre companies, and after school classes in Kurdish to help children with schoolwork were all closed.

The Kurdish Institute of Istanbul itself was shut down by presidential decree in 2017, and was succeeded by the Kurdish Research Association. Efforts to support Kurdish language education have been maintained by several activist groups and NGOs. Istanbul’s centre-left secular mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, who secured his victory against the AKP with a significant boost from Kurdish voters, also announced free Kurdish courses offered by the municipality.

The Duolingo Kurdî team believe interest in their course could reach hundreds of thousands of people. They are in contact with many linguistic experts, and also want to expand to a Kurdish-English course, which has seen increased demand in recent years especially due to the popularity of Kurdish fighters in northern Syria who were integral in the international effort against ISIS.

“There is a significant interest in Kurdish here because of the U.S.-Kurdish relationship, the Kurdish question, and – among the left – the political project in Rojava,” a forum user wrote, using the Syrian Kurdish name for the region.

“The dearth of Kurdish learning materials has been the case for a long time,” wrote another forum user. “It is interesting that the language of one of the few U.S. allies in the Middle East – for good or for ill – is a language that is almost impossible to study in the U.S. “

There are Kurdish grammar books, but not many examples of exercises, Xecê Meşkubar, a member of the Duolingo Kurdî team and a Kurdish teacher for English speakers, told Ahval. She has started to prepare her own, and is sharing her notes with thousands of people around the world.

“Another difficulty is that people are not aware of standardised Kurdish,” Meşkubar said. Kurdish dialects diverge into countless branches throughout Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria due to efforts by these states to suppress the language, as well as the lack of a central standardisation authority.

That is where organisations like the Kurdish Institute of Istanbul came in. Since 1992, the institute prepared and published dictionaries between Turkish and Kurdish at several levels, an idioms dictionary, several grammar books, learning guides, and textbooks for classes. It has also translated into several dialects classic literature from around the world, and a 12-book set of Kurdish fairy tales for children.

Kurdish remained relatively strong despite decades of suppression and a lack of a protective body due to the specific characteristics of the people who speak it. Until the 1990s, when several million Kurds were forced out of their villages due to fighting between Turkey and the PKK, the country’s Kurdish population remained largely homogenous in the eastern and southeastern parts of the country.

In the past it was often only men who dealt with the outside world who learned Turkish, with few exceptions, leading to many women not speaking Turkish very well, if at all. Generations of extended families remained close, and young people learned their first words in Kurdish from their elder caretakers.

In recent years, migration, losing extended family ties in urban centres, increased domination of Turkish-language media facilitated by technological development, increased number of marriages with partners outside of the Kurdish community, and a lack of professional/financial incentive to learn the language has resulted in fewer young people speaking Kurdish, Beyaz said. “This serious matter could lead to grave consequences if it is not solved in the next decade.”

Kurds demand education in Kurdish, and even its acknowledgement as a second official language in majority-Kurdish regions, “because they know that a language cannot survive and thrive if it is not used in public life, official correspondence, politics, media, economy, education, scientific research and technology,” he added.

A reason for the pressure on the language seems to be a fear of separatism on the Turkish side. One message on the Duolingo forum thread read: “I want to say ‘lay down arms, stop or I will shoot you etc.’ in their own language,” and the post’s author said he had a problem with “Kurdish-speaking terrorists.”

In response to this sentiment, Beyaz told Ahval: “On the contrary, the guarantee of peaceful coexistence lies not in oppressing another identity and usurping its rights, but in providing free and equal conditions for that identity to develop a sentiment and consciousness of a common motherland and a common democratic state.”

Source: Ahval