What the Kurds want in Turkey and Syria

Democratic Autonomy aims at achieving a way for ethnic, religious and other social groups to peacefully live together without fear of violence, assimilation and oppression.

After playing a key role in the fight against the Islamic State, Kurdish organisations from Syria and Turkey have gained an international reputation of courage and solitude. But only their military successes are recognized today – their political demands for self-government, regional autonomy, egalitarian coexistence have not been widely heard, and their political aims are still being questioned.

Yet it is clear what they want. In both Turkey and Syria, they are pursuing a political approach for the non-violent solution of the Kurdish question. This approach has been developed since the year 2000 by the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Abdullah Öcalan: Democratic Autonomy.

A grand experiment in Democratic Autonomy took place over recent years in the three geographically disconnected cantons in the north of Syria known as Rôjava, where Kurdish-led organisations with links to the PKK helped set up an autonomous system of government.

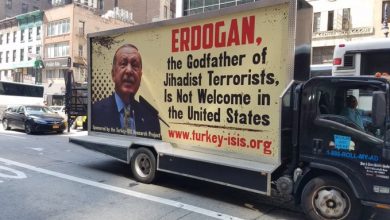

The Turkish government dealt a crippling blow to the project by launching a military operation last month to drive the Kurds away from its border. Ankara views the PKK as a terrorist organisation and says the presence of allied groups on its border was a security threat, but many believe the real threat to the Turkish government was the existence of an autonomous Kurdish-led region.

Although the Kurds in Turkey are also exposed to enormous state violence and emotionally detach themselves from Turkey, Kurdish political representatives still insist on this approach, which precludes an independent Kurdish state and presupposes democratic coexistence with Turkey and Syria. This approach marks the fourth strategic era of the Kurdish movement, which calls it a “revolutionary struggle of the people”.

The end of the Soviet Union and the increasing awareness that the PKK’s war against the Turkish state since 1984 had resulted in a stalemate led the Kurdish movement to rethink its strategies and key principles.

Most centrally, the goal of national independence from the Turkish state was replaced by the concept of Democratic Autonomy, which draws on the concepts of communalism and confederalism laid out by libertarian thinker Murray Bookchin.

This has been proposed as a model to decentralize the state and achieve radical changes in gender equality, ecology and communal economy. It attempts to return the powers of governance to the hands of the people by implementing structures of direct democracy, while demanding recognition through a status of autonomy within the given state.

In this sense, this model is first of all an answer to the critique of nation states generally, with their homogenising and exclusionary principals of citizenship and centralist styles of government, and of Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq more specifically, which have tried to deny the existence of the Kurds and other religious and ethnic groups, such as Alevis, Yezidis and Assyrians. Each of these minorities has faced brutal attempts to wipe them out and assimilate them.

In contrast to Bookchin’s model, the Kurdish Democratic Autonomy not only relies on neighbourhood assemblies but on radically transformed mechanisms for bottom-up decision-making, which include assemblies categorised according to social affiliation, such as gender, age, ethnic and faith groups. These are interlinked via a tiered delegate system of district and country-wide councils.

Democratic Autonomy aims at achieving a way for ethnic, religious and other social groups to peacefully live together without fear of violence, assimilation and oppression.

This model differs from other programmes of bottom-up change in that the Kurdish movement is neither waiting until after a radical turnover of government, a revolution, nor the moment of national liberation, but instead aims to democratically establish the necessary instruments and mechanisms for de facto self-government.

The Kurdish movement has begun to institutionalize a system of assemblies and councils on the level of villages and neighbourhoods, district and city councils, as well as for women, youth, religion, and ethnicity, whose delegates come together in people’s assemblies.

This has taken place both under the Movement for a Democratic Society umbrella group in Rôjava and in the southeast Turkish regions known as Northern Kurdistan under the Democratic Society Party, which was banned by the Turkish state in 2009 over links to the PKK.

In doing so, the Kurdish Movement in Turkey made use of given state institutions including elected municipalities where Kurdish parties have been increasingly successful over the past decade. The municipalities were especially vital, for instance, in establishing alternative educational, social, health and poverty aid institutions, and also initiated alternative economic endeavours such as women’s cooperatives.

The establishment of these institutions and mechanisms is a process in the making and entails numerous difficulties. In Syria, this process has been impeded less by the Syrian state than by the fight against ISIS and the attacks by Turkey.

The civil war enabled a situation in which Rôjava was able to declare itself an autonomous region within Syria in 2012, giving itself a constitution called the “social contract” and establishing its own institutions. Many of the communes established in Rôjava work far more independently than those in Turkey, attending to questions of electricity, provision of food, organising the support of the poorest of the community with fuel and other basic needs, as well as discussing and solving other social problems.

Some have erected communal cooperatives including bakeries, sewing workshops or agricultural initiatives. They have commissions for the organisation of defence, justice, infrastructure, ecology, youth, as well as economy. All those are now being attacked and destroyed by Turkish forces and their Syrian rebel allies.

Putting an end to patriarchal structures and thought is particularly central for the Kurdish movement. The idea that no revolution can occur without a radical change in respect to gender equality has been greatly emphasised. Consequently, women are present in all parts of decision-making processes through the 40 percent quota and a co-chairperson system, which means that all central positions are held by both a man and a woman. Women-only committees have authority in all women’s questions and women are deliberately integrated in armed self-defence and have their own military wing in Rôjava.

In Turkey, the establishment of these structures of Democratic Autonomy has been violently impeded, especially through the mass detention of local and regional leaders of the legal Kurdish party as well as elected mayors, local governors (muhtars), members of parliament, lawyers, prominent academics and journalists. All of those charged are accused of links to or making propaganda for a terrorist organisation, namely the PKK.

This underlines how strongly challenged the Turkish state feels by this form of democratisation, which side-lines its institutions by implementing alternative structures. In this sense, this model of Democratic Autonomy is the de facto establishment of self-government. Thus, this struggle for autonomy creates its own spaces for participative democracy despite and within the state, which is the trouble for Turkey and Syria.

Source: Ahval